INSIGHTS

by Anna Grochowska

Ecoart

“It would be possible to describe everything scientifically, but it would make no sense; it would be without meaning, as if you described a Beethoven symphony as a variation of wave pressure.”

Albert Einstein

The case for interconnection in ecoart

“Rigor alone is paralytic death, but imagination alone is insanity,” Gregory Bateson wrote in Mind and Nature, a book he wrote in early 2000 and where in he beautifully touches the subjects of connectivity and patterns that relate all living things, enriching the grounds which give understanding to ecoart as a way of describing challenges we face in the universe.

Over the past years, climate change, degradation of nature, environmental crises, resources shortages and many other complex issues across the world. Those problems need to be somehow addressed to maintain our presence on the planet and keep the world habitable for future generations. Although supported by an enormous number of studies, very often, the problems we encounter are analyzed in separate technical and scientific disciplines. As a result, the knowledge derived from the research stays isolated and spreads only amongst the narrow field of specialists. In recent times, many authors have argued that in the face of climate crisis we can no longer afford to look at the problems with blinkers. The art, science and technology disciplines need to communicate with one another and exchange perspectives. In his philosophical book, The Three Ecologies, Félix Guattari (psychoanalyst, philosopher and dedicated activist) emphasized the necessity of understanding connections between the cultural and environmental spheres:

“Now more than ever, nature cannot be separated from culture; in order to comprehend the interactions between ecosystems, the mechanosphere and the social and individual Universes of reference, we must learn to think ‘transversally'”

When closely pondered, Guattari words echo the principal concepts of ecology, which, according to most authoritative definitions, is the branch of biology that deals with the relations of organisms to one another and to their physical surroundings. In fact, the original framing of the word ecology comes from philosopher Ernst Haeckel, who wrote in 1870: “By ecology we mean the body of knowledge concerning the economy of nature—the investigation of the total relations of the animal both to its inorganic and to its organic environment”. Although the definitions of ecology in modern literature now slightly vary, all of them embrace the concept of interconnection.

In another example of that case, ecologist Frank B. Golley, in his book about the ecosystem concept, describes its usefulness in broad terms:

“[Ecology] emphasized interconnection and integration of systems at a variety of scales, cooperation, synergisms and symbioses rather than dialectical opposition, competition and conflict […] Thus the ecosystem perspective can lead towards an ecological philosophy, and from philosophy it can lead to an environmental value system, environmental law and a political agenda.”

Glendurgan Garden, United Kingdom (photo: Benjamin Elliott)

Drawing a definition: what is ecoart?

That views on ecology embrace the importance of connection and open the way to new approaches, notably ecoart. Emerging as an artistic discipline that uses the power of the humanities to enrich scientific knowledge, Eco-art thrives on the fields based on environmental science and adds layers of imagination and expressiveness connecting with human emotion to bring the issues closer to people and create a greater impact. This special genre of art leans on the need to address both Man’s and Nature’s needs, and extends over the fields of environmental science, philosophy and sustainability. Ecoart can thus play an important role by connecting the chief disciplines and offering new narratives for our future, both helpful for the world of science and humanities.

In their book Introduction to the Environmental Humanities, J. Andrew Hubbell and John C. Ryan define ecological art (ecoart) as the art that “situates creative practices within ecological patterns, processes, systems, relations, and ethics”. Also referred to as ecological art, this discipline draws on the concepts derived from ecology, science, the ecosystems, biodiversity and sustainability, tackling the goal of meeting the problems of nature’s ecosystems.

Since ecological art is made to embrace interconnections between many disciplines, which are usually existing in isolation, it poses fundamental questions of values, culture, history, philosophy and attempts to frame the environmental problems and describe it in a humanistic way. In the same book, Hubbell and Ryan argue:

“While the sciences can be unmatched in describing the environmental chance and crisis, the humanities allow us to think more about the moral, ethical, and social dimensions of environmental change and crisis. They enable us to respond to ecological degradation and the dangers of human development and progress in ways that complicate, complement, and extend scientific inquiry. “

Contrary to other genres, though, ecoart moves beyond the focus on the aesthetic or visual representation of nature; it instead concentrates on embracing creative efforts akin to ecological thinking, philosophy, science and ethics. In this sense, it in turn becomes ecological in its very character.

Sediment in the Gulf of Mexico off the Louisiana coast. Photo: United States Geological Survey

Art of ecologic intervention

Ruth Wallen, an interdisciplinary artist and writer, describes ecoart as “a call for visionary intervention in a time of crisis”. This statement, key to ecologic art, evokes the concept of “ecovention” proposed in 1999 and inherently linked to the discipline. Ecovention is a fusion of the words ecology, innovation and intervention, alluding to the kinds of art that are made in degraded natural territories and which aim at increasing public consciousness, pointing out to practical solutions and igniting social, ecological and technical inspiration.

A brilliant example of this, leaning on thorough scientific and natural background, is the Revival Field project located in the American State of Minnesota. Quoted by many critics as “now a classic model for the partnership of art and environmental science” (Eleanor Heartney), this project made by Mel Chin was inspired by the research on plants that have a capability of pulling heavy metals from the soil.

The project emerged as a response to environmental problem of landfill in Minnesota, which for years has been heavily polluted by the dumping of industrial and domestic waste (including car and battery waste), leading to the classification of the area as a potential threat to public health and the environment. Mel Chin’s project relied on the principles of phytoremediation. As a way of its ecovention, the artist designed a green plot filled with the dedicated plants, a sort of a crosshair target marking the area of remediation. Alluding to the artistic techniques of reductive sculpting, in which the materials are carved by the chosen medium, Chin conceived the contaminated soil as a block of material, and the plants used as a sculpting tool. The imagery of Chin’s ecoart have been interpreted on many levels, including the symbolism of the circle and its division into quadrants and sections. But one of its most important features was promoting the use of scientific solutions to create a positive environmental impact, while cooperating across artistic and technological disciplines.

The Revival Field project provides an extraordinary proof of art and science converging and conveying new concepts. Since its installation, phytoremediation has become an increasingly studied and applied area of scientific investigation, as well asa large industry. It demonstrates the spirit of ecological art and the importance of the contribution it can make, one that is echoed by Ilya Prigogine in his book Is future given?, discussing fundamental challenges of science and philosophic concepts:

“The understanding of complexity and the use of the creativity of nature, the continuation of the work of nature are the grand challenges for the scientists of the 21st century.”

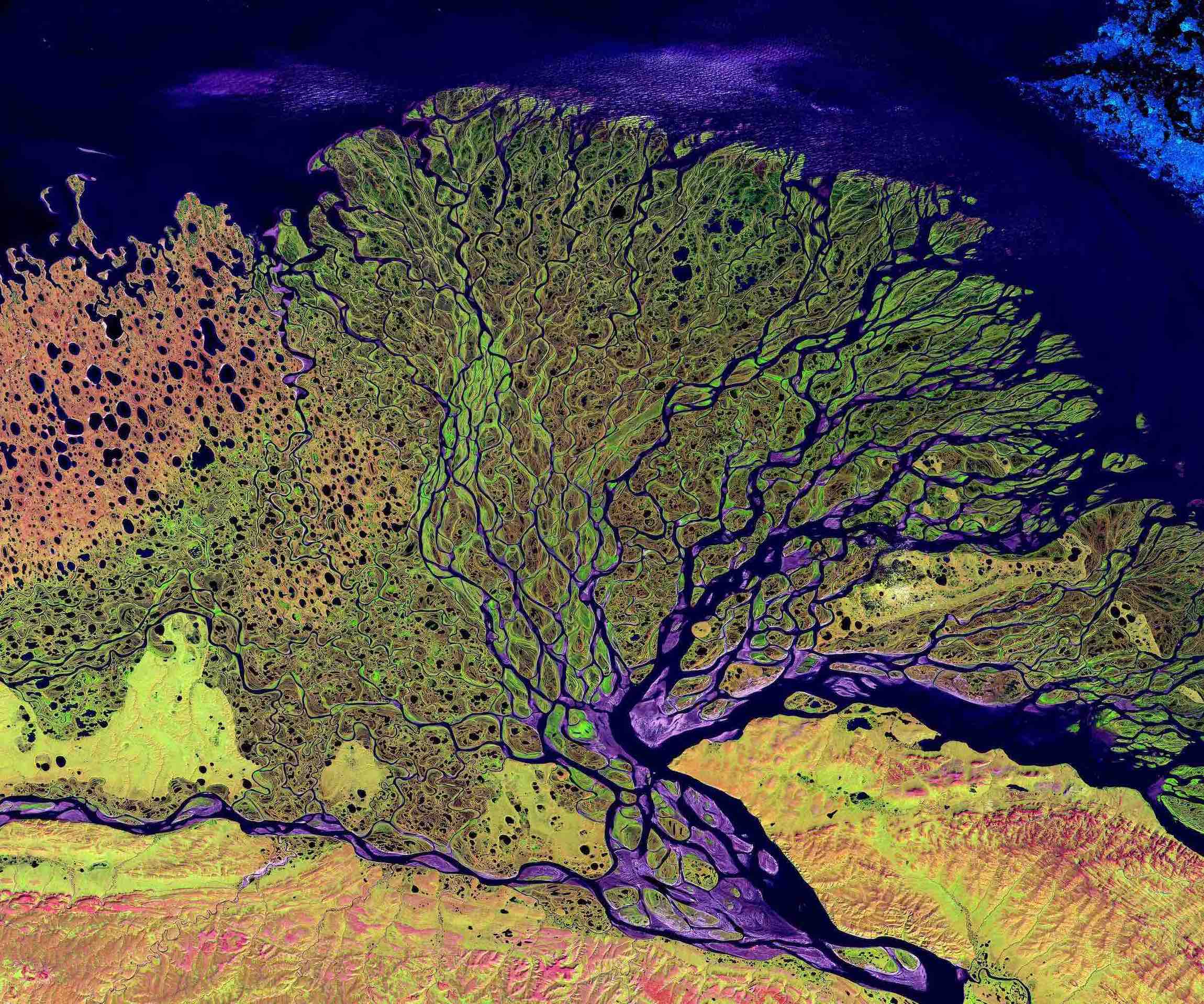

The Lena River Delta Reserve, the most extensive protected wilderness area in Russia and one of the largest rivers in the world. Photo: United States Geological Survey

Ecoart among the environmental arts

Many artists, via their work, believe that the challenges around climate change can be addressed in a way that goes far beyond illustrating theories and problems. In their view, ecoart can promote a fruitful dialogue around environmental issues and viable, meaningful answers to them. Multiple art movements and genres related to the environmental humanities have thus been emerging. J. Andrew Hubbell andJohn C. Ryan, in their book, provide a more complex distinction of them.

At Vadviam, we aspire to promote, exhibit and interconnect the scientific, social and artistic initiatives centered around the future, liveability and sustainability of our world. By interconnecting the stories of technology, engineering, the arts and literature, we make a case for the humanities as a means to discover what should be our guiding lights in the modern world. Learn more about our approach here (link).

A humanistic approach to complex challenges

Ecoart vividly exemplifies how the world of art can play a constructive role in the development of sustainability practices. It creates a common pattern for the world of science, technology and culture, embracing the complexity and challenges of each and making the case for a humanistic approach in the engineering world. It explores the relations between art and ecology and promotes a sound analytic approach behind the artistic creation. It embraces ecological citizenship in a world where human responsibility for the environment is, or should be, amoral imperative.

“All religions, arts and sciences are branches of the same tree. All these aspirations are directed toward ennobling man’s life, lifting it from the sphere of mere physical existence and leading the individual towards freedom.”

– Albert Einstein

Ecoart, ecological art (photography by Vadviam, 2022)

References

- J. Andrew Hubbell, John C. Ryan, Introduction to the Environmental Humanities, 2021

- Frank B. Golley, A History of the Ecosystem Concept in Ecology, 1993

- Félix Guattari, The Three Ecologies, 1989

- G. Bateson, Mind and Nature – a Necessary Unity, 1979

- R. Wallen, Ecological Art: A Call for Visionary Intervention in a Time of Crisis, 2012

- E. Heartney, Art for the Anthropocene era, 2014

- Mel Chin, Revival Field, 1991

About us

Vadviam connects knowledge of environmental matters with a passion for social progress. By combining years of experience in industrial decarbonisation with novel approaches to articulating sustainability, we help companies to enhance and communicate their performance in this field.